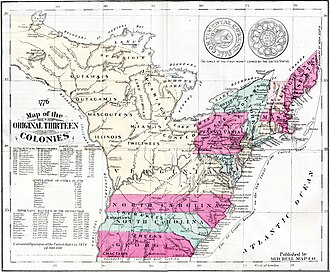

An Introduction to the Thirteen American Colonies

Before the United States existed as a nation, it existed as a collection of distinct colonies—each with its own founding purpose, social character, economy, and relationship to Britain. The Thirteen American Colonies, established along the Atlantic seaboard between the early seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, were never a single, unified project. They differed sharply in religion, labor systems, settlement patterns, and political culture.

Yet it was precisely this diversity that shaped the American experience. When tensions with Britain escalated in the eighteenth century, these colonies—often divided among themselves—were forced to discover common ground. Understanding the origins and character of each colony provides essential context for understanding the American Revolution, the framing of the Constitution, and the enduring regional differences within the United States.

What follows is a brief overview of each of the thirteen colonies, intended as a foundation for deeper exploration in future posts.

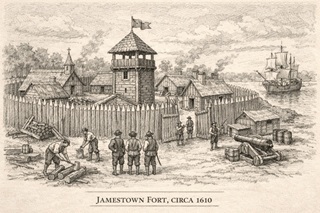

Virginia (1607)

Virginia was the first permanent English colony in North America, founded at Jamestown in 1607. Initially struggling with starvation, disease, and conflict with Indigenous peoples, the colony eventually stabilized through the cultivation of tobacco. Tobacco became the economic engine of Virginia and shaped its social structure, encouraging large plantations and the expansion of enslaved labor.

Virginia developed a powerful landowning elite and early traditions of self-government, including the House of Burgesses. Its influence on colonial politics—and later on the founding of the United States—was immense.

Massachusetts (1620 / 1630)

Massachusetts was founded by English Puritans seeking to build a godly society. The Plymouth Colony (1620) and the Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630) eventually merged, forming the cultural heart of New England. Religion played a central role in daily life, education, and governance.

With a diversified economy based on fishing, trade, shipbuilding, and small farms, Massachusetts developed strong towns and institutions. Its emphasis on literacy and moral order left a lasting mark on American culture.

New Hampshire (1623)

Originally settled as a fishing and trading outpost, New Hampshire developed slowly and often fell under the influence of neighboring Massachusetts. Its economy relied on fishing, timber, and small-scale agriculture.

New Hampshire’s scattered settlements and limited resources meant it played a quieter role in colonial affairs, but its residents nonetheless shared New England’s strong traditions of local governance and independence.

Maryland (1634)

Maryland was founded as a haven for English Catholics under Lord Baltimore. Although Catholics never formed a majority, the colony became known for its early commitment to religious toleration, embodied in the Maryland Toleration Act of 1649.

Like Virginia, Maryland relied heavily on tobacco and plantation agriculture, leading to the widespread use of enslaved labor. Its experiment in religious coexistence remains one of its most important legacies.

Connecticut (1636)

Founded by Puritan settlers moving west from Massachusetts, Connecticut emphasized self-rule and community governance. The Fundamental Orders of Connecticut (1639) are often cited as one of the earliest written constitutions in the Western world.

The colony prospered through farming, trade, and craftsmanship. Its political traditions reflected a strong belief in representative government and local autonomy.

Rhode Island (1636)

Rhode Island was founded by Roger Williams, who had been expelled from Massachusetts for advocating religious freedom and separation of church and state. The colony became a refuge for religious dissenters of all kinds.

More tolerant and less socially rigid than its neighbors, Rhode Island relied on trade, shipping, and small farms. Its early commitment to religious liberty would later influence American constitutional principles.

Delaware (1638)

Originally settled by the Dutch and Swedes before coming under English control, Delaware was small but strategically located. Its fertile land supported agriculture, while its ports facilitated trade.

Delaware often shared a governor with Pennsylvania but maintained its own assembly. Its mixed cultural heritage reflected the diversity of the Middle Colonies.

New York (1624)

Founded by the Dutch as New Netherland and later seized by the English, New York was one of the most diverse colonies. Its population included Dutch, English, Germans, Africans, and Indigenous peoples.

With a strong commercial economy centered on New York City, the colony played a crucial role in Atlantic trade. Its diversity fostered a degree of tolerance, but also social tension and inequality.

New Jersey (1664)

New Jersey began as a proprietary colony and attracted settlers from various backgrounds. Its fertile soil made it well suited to farming, particularly grain production.

Often overshadowed by New York and Pennsylvania, New Jersey nonetheless developed a stable agricultural economy and participated actively in regional trade networks.

Pennsylvania (1681)

Founded by William Penn as a Quaker refuge, Pennsylvania became one of the most prosperous and tolerant colonies. Penn’s “Holy Experiment” emphasized religious freedom, fair treatment of Indigenous peoples, and representative government.

Philadelphia grew into one of the largest cities in colonial America, serving as a center of commerce, printing, and political thought. Pennsylvania’s ideals would later influence revolutionary and constitutional debates.

North Carolina (1663)

North Carolina developed more slowly than its southern neighbors. Settled largely by small farmers, it lacked the large plantations and wealthy elites found elsewhere in the South.

Tobacco and subsistence farming dominated the economy. The colony’s independent-minded settlers often clashed with colonial authorities, foreshadowing later resistance to centralized control.

South Carolina (1663)

South Carolina developed a plantation economy based on rice and indigo, relying heavily on enslaved African labor. Its wealth was concentrated among a small planter elite, particularly around Charleston.

The colony’s social hierarchy was rigid, and racial divisions were especially pronounced. South Carolina’s economy tied it closely to global trade networks and British commercial interests.

Georgia (1732)

Georgia was the last of the thirteen colonies to be founded. Established as a buffer against Spanish Florida and as a haven for debtors, it initially banned slavery and large landholdings.

These restrictions were eventually lifted, and Georgia came to resemble South Carolina in its plantation-based economy. Its strategic location made it important militarily and politically.

Looking Ahead

The thirteen colonies were united by geography and language, but divided by culture, economy, and belief. Understanding these differences is essential to understanding why cooperation was so difficult—and why it was so remarkable when it finally occurred.

In future posts, we will examine each colony in greater depth, exploring how local conditions shaped political ideals, social structures, and responses to British authority. The story of American independence begins here—not with a single revolution, but with thirteen very different worlds learning, slowly and imperfectly, how to act as one.