The History of the Virginia Colony, 1607–1775

From Fragile Outpost to Revolutionary Keystone

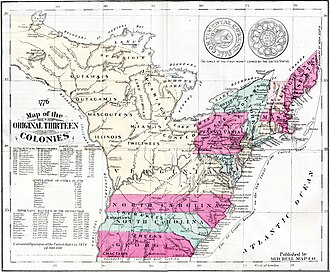

The story of the Virginia Colony is, in many ways, the story of early English America itself. Founded in uncertainty, shaped by hardship, and transformed by ambition, Virginia evolved over nearly two centuries from a precarious coastal settlement into the largest, wealthiest, and most politically influential of Britain’s mainland colonies. By 1775, Virginians stood at the forefront of resistance to imperial authority, producing leaders, ideas, and institutions that would guide the American Revolution.

Understanding Virginia’s colonial history requires more than recounting famous names or dramatic events. It means tracing how geography, labor systems, political culture, and economic priorities interacted over time—often with consequences that colonists neither anticipated nor controlled. From the founding of Jamestown to the eve of independence, Virginia was both a laboratory of empire and a proving ground for American self-government.

The Founding of Jamestown, 1607

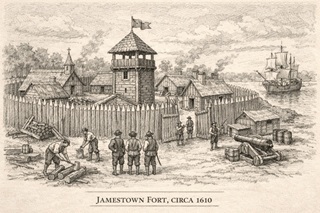

Virginia’s colonial history begins in 1607 with the establishment of Jamestown, the first permanent English settlement in North America. Sponsored by the Virginia Company of London, the expedition was motivated less by religious idealism than by the promise of profit. Investors hoped the colony would yield gold, discover a passage to Asia, or produce valuable commodities for export.

The site chosen along the James River was defensible but deeply flawed. The marshy environment bred disease, the water was brackish, and food supplies were uncertain. Within months, hunger, illness, and internal conflict threatened the colony’s survival. Leadership was often unstable, and relations with the local Powhatan Confederacy alternated between uneasy trade and violent confrontation.

Only the imposition of strict discipline—most famously under John Smith—and continued resupply from England kept Jamestown alive. Even so, the “Starving Time” of 1609–1610 reduced the population from several hundred settlers to a few dozen survivors. Virginia’s early years were marked not by triumph, but by persistence in the face of near collapse.

Tobacco and the Transformation of the Colony

Virginia’s fortunes changed dramatically with the introduction of tobacco cultivation in the 1610s. John Rolfe’s successful experimentation with a milder strain of tobacco created a product eagerly sought by English consumers. Tobacco quickly became the economic foundation of the colony, reshaping nearly every aspect of Virginian life.

Planting tobacco required land, labor, and access to waterways for export. Settlers spread outward along rivers, creating dispersed plantations rather than compact towns. This settlement pattern weakened centralized authority but strengthened local autonomy. Land ownership became the primary marker of status, and political influence increasingly flowed from economic success.

Tobacco’s profitability also intensified conflict with Indigenous peoples, as settlers encroached on Native land to expand cultivation. Over time, cycles of violence and displacement became a grim feature of Virginia’s growth, culminating in devastating wars that permanently altered the region’s demographic and political landscape.

The Rise of Self-Government: The House of Burgesses

In 1619, Virginia established an institution that would have profound long-term consequences: the House of Burgesses, the first representative legislative body in English America. Though initially limited in power and subject to the authority of the Virginia Company and later the Crown, the House of Burgesses allowed local elites to participate directly in governance.

This development reflected practical necessity. The distance from England made direct rule inefficient, and colonial leaders needed local cooperation to maintain order and encourage settlement. Over time, Virginians came to view representative government not as a privilege granted by the Crown, but as a customary right.

The tradition of local political participation fostered a strong sense of autonomy among Virginia’s planter class. While loyalty to the monarchy remained genuine for much of the seventeenth century, expectations of self-rule were already deeply rooted.

Labor Systems: From Indentured Servitude to Slavery

Tobacco cultivation created an insatiable demand for labor. In the early decades, Virginia relied primarily on indentured servants—Europeans who exchanged years of labor for passage to the New World. Indentured servitude allowed many poor Englishmen to acquire land after completing their terms, contributing to a relatively fluid social structure in the colony’s early years.

By the late seventeenth century, however, this system began to change. Rising life expectancy made lifelong labor more economically attractive than temporary servitude, and England’s improving economy reduced the supply of willing indentured servants. At the same time, colonial laws increasingly defined Africans and their descendants as enslaved for life.

By the early eighteenth century, Virginia had become a slave society. Enslaved Africans formed a growing proportion of the population, and racialized slavery became central to the colony’s economy and social order. This transformation hardened class divisions and institutionalized racial hierarchy—developments that would shape Virginia’s history long after independence.

Bacon’s Rebellion and Political Tensions

The colony’s evolving social structure was tested dramatically during Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676. Led by Nathaniel Bacon, a young planter, the rebellion drew support from small farmers, former servants, and frontier settlers frustrated by economic inequality, limited political access, and the colonial government’s perceived failure to protect them from Indigenous attacks.

Though Bacon died before the rebellion could succeed, the uprising exposed deep tensions within Virginian society. Governor William Berkeley eventually restored order with royal assistance, but the message was clear: social unrest posed a real threat to colonial stability.

In response, Virginia’s elite accelerated the shift toward racial slavery, which reduced reliance on volatile former servants and helped unify white colonists across class lines. While Bacon’s Rebellion failed militarily, it reshaped the colony’s labor system and political calculations.

Virginia as a Royal Colony

In 1624, Virginia became a royal colony, bringing it under direct control of the Crown. Royal governors represented imperial authority, but they governed in partnership—often uneasy—with the House of Burgesses and local elites.

Throughout the eighteenth century, Virginia developed a powerful planter aristocracy. Families such as the Washingtons, Lees, Randolphs, and Carters accumulated vast estates and dominated political life. Their wealth allowed them to educate their sons, cultivate transatlantic connections, and assume leadership roles in both colonial and imperial affairs.

Despite social inequality, Virginia’s political culture emphasized honor, local authority, and resistance to arbitrary power. Governors who attempted to override established practices often faced stiff opposition, reinforcing a tradition of negotiated governance rather than imposed rule.

Religion and Culture in Colonial Virginia

Unlike New England, Virginia was not founded for religious reasons. The Church of England was established by law, but religious observance was often lax, especially in rural areas. Anglican parishes served administrative as well as spiritual functions, collecting taxes and maintaining social order.

The eighteenth century brought religious change with the rise of dissenting movements, particularly Baptists and Presbyterians. These groups challenged the authority of the established church and promoted ideas of religious liberty and moral equality. Their growing influence unsettled Virginia’s elite and contributed to broader debates about freedom and authority.

Culturally, Virginia developed a strong attachment to English traditions, literature, and law. At the same time, the realities of frontier life and plantation society fostered a distinct colonial identity—one that valued independence, landownership, and personal reputation.

The Westward Vision and Expansion

By the mid-eighteenth century, Virginia’s ambitions extended far beyond the Tidewater region. Virginians looked westward across the Appalachian Mountains, envisioning land, wealth, and opportunity. This expansion brought conflict with Indigenous nations and competing European powers, particularly France.

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) had profound consequences for Virginia. Many Virginians, including a young George Washington, gained military experience during the conflict. While Britain’s victory secured vast new territories, it also left the empire deeply in debt.

To manage its new possessions and recover costs, Britain imposed new taxes and regulations on the colonies. For Virginians accustomed to relative autonomy, these measures felt like unwelcome intrusions.

Growing Resistance to British Authority

In the years following the French and Indian War, tensions between Virginia and Britain escalated. Acts such as the Stamp Act and the Townshend Duties provoked protests from the House of Burgesses, which asserted that only colonial assemblies had the right to tax colonists.

Virginia played a leading role in articulating constitutional arguments against parliamentary overreach. Figures like Patrick Henry emerged as powerful voices of resistance, framing imperial policies as threats to liberty rather than mere financial burdens.

The Crown’s dissolution of the House of Burgesses in response to protest resolutions only deepened colonial resentment. Virginians increasingly organized outside official channels, forming committees of correspondence and extra-legal conventions that coordinated resistance across the colonies.

Toward Revolution, 1775

By 1775, Virginia stood on the brink of revolution. The colony’s long experience with self-government, its powerful planter leadership, and its growing sense of American identity positioned it at the forefront of the coming conflict.

The clash at Lexington and Concord galvanized Virginian opinion, and the colony soon mobilized its militia and political institutions in support of resistance. Though independence was not yet universally embraced, loyalty to Britain had eroded beyond repair.

Virginia’s colonial journey—from a fragile outpost struggling to survive, to a confident society ready to challenge imperial authority—reveals the slow, cumulative nature of historical change. The Revolution did not arise suddenly in 1775; it emerged from generations of experience, conflict, compromise, and adaptation.

Conclusion: Virginia’s Colonial Legacy

Between 1607 and 1775, the Virginia Colony underwent a profound transformation. Economic innovation, political experimentation, social stratification, and territorial expansion shaped a society both deeply English and increasingly American.

Virginia’s legacy is complex and often contradictory. It produced ideals of liberty alongside systems of oppression, institutions of self-rule alongside entrenched inequality. Yet its influence on the American Revolution—and on the nation that followed—is undeniable.

To understand Virginia is to understand the foundations of American history itself: a story of ambition and endurance, shaped as much by unintended consequences as by deliberate design.