The Historical Impact of Lord Byron’s Poetry

Few poets have lived so intensely in the public imagination—or left so visible a mark on culture, politics, and literary identity—as Lord Byron. Writing at the height of the Romantic movement, Byron transformed poetry into a force that spilled far beyond the page. His verse reshaped ideas of individual freedom, political resistance, emotional authenticity, and even celebrity itself. To read Byron is not only to encounter a powerful poetic voice, but to witness the emergence of modern attitudes toward art, rebellion, and selfhood.

This essay explores the historical impact of Byron’s poetry across literature, politics, culture, and national identity, tracing how his work helped redefine what poetry could do—and what a poet could be.

Romanticism and the Age of Upheaval

Byron came of age during a period of profound instability. The French Revolution had shaken Europe’s political foundations, the Napoleonic Wars had redrawn borders, and industrialization was beginning to transform daily life. Romanticism emerged as both a response and a rebellion: against Enlightenment rationalism, against social conformity, and against the narrowing of human experience to utility and reason.

While Romantic poets often emphasized nature, emotion, and imagination, Byron stood apart for his unapologetic engagement with the political and social crises of his time. His poetry does not retreat from history; it wrestles with it. Unlike more inward-looking Romantic voices, Byron fused lyric intensity with satire, historical awareness, and moral outrage.

This fusion made his poetry feel dangerous—alive with the tensions of its age—and ensured its wide resonance across Europe and beyond.

The Invention of the Byronic Hero

Perhaps Byron’s most enduring literary contribution is the creation of the Byronic hero, a figure that would echo through nineteenth- and twentieth-century culture. This character—brooding, alienated, morally ambiguous, emotionally wounded, and defiantly individual—appears in works such as Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, The Corsair, and Manfred.

The Byronic hero represented a sharp departure from earlier literary ideals. Instead of virtue rewarded and vice punished, Byron offered protagonists who carried guilt without repentance, suffering without consolation, and pride without apology. These figures were shaped as much by inner turmoil as by external conflict.

Historically, this was revolutionary. Byron gave voice to a modern psychological sensibility: the idea that identity is fractured, that moral certainty is elusive, and that rebellion may be inseparable from self-destruction. Writers from Fyodor Dostoevsky to Oscar Wilde would later draw upon this template, adapting it to new philosophical and cultural contexts.

Beyond literature, the Byronic hero influenced popular notions of masculinity—replacing stoic restraint with emotional depth and moral complexity—and helped normalize the idea that suffering itself could be a form of authenticity.

Poetry as Political Resistance

Byron’s poetry was inseparable from his politics. Fiercely opposed to tyranny, hypocrisy, and moral complacency, he used verse as a weapon against entrenched power. His satirical masterpiece Don Juan skewers aristocratic pretension, sexual double standards, religious hypocrisy, and imperial arrogance with relentless wit.

Unlike poets who cloaked political critique in abstraction, Byron named names, mocked institutions, and exposed contradictions. His verse circulated widely, reaching audiences far beyond academic or elite literary circles. In doing so, Byron helped redefine poetry as a medium for political engagement rather than moral instruction alone.

His opposition to oppression was not merely rhetorical. Byron’s poetry inspired nationalist and liberal movements across Europe, particularly in Italy and Greece. For readers living under authoritarian regimes, his work articulated a powerful emotional vocabulary of resistance—anger, longing, irony, and defiance.

Poetry, in Byron’s hands, became an instrument of historical pressure: a way of keeping revolutionary ideals alive even when revolutions themselves had failed.

The Poet as Public Figure

One of Byron’s most significant historical impacts lies not only in what he wrote, but in how he lived—and how that life was publicly consumed. Byron was arguably the first modern literary celebrity. His fame was instantaneous, international, and inseparable from scandal.

When Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage was published in 1812, Byron famously remarked, “I awoke one morning and found myself famous.” Readers devoured not just his poetry, but rumors of his affairs, his exile, his defiance of social norms. This fusion of art and persona created a new model of authorship in which the poet’s life became part of the work.

Historically, this marked a turning point. Byron helped establish the idea that artists could—and perhaps should—live outside conventional morality. Later figures such as Percy Bysshe Shelley, Charles Baudelaire, and even modern rock musicians inherited this model of creative transgression.

The consequences were double-edged. Byron’s example expanded artistic freedom, but it also introduced a culture of voyeurism and moral sensationalism that still shapes celebrity today.

Language, Irony, and the Modern Voice

Stylistically, Byron transformed poetic language by embracing irony, conversational tone, and self-awareness. His verse often mocks its own seriousness, undercuts heroic posturing, and exposes the artificiality of moral certainty. In Don Juan, particularly, Byron deploys a voice that feels startlingly modern—playful, cynical, intimate, and unpredictable.

This tonal flexibility had enormous historical influence. It loosened the formal rigidity of poetic diction and made room for a voice that could be simultaneously lyrical and skeptical. Later poets—from Alexander Pushkin to W. H. Auden—would build upon Byron’s example, blending wit with seriousness and emotion with detachment.

Byron demonstrated that poetry need not preach or idealize to be profound. It could question itself, laugh at its own ambitions, and still speak powerfully to the human condition.

Byron and National Liberation

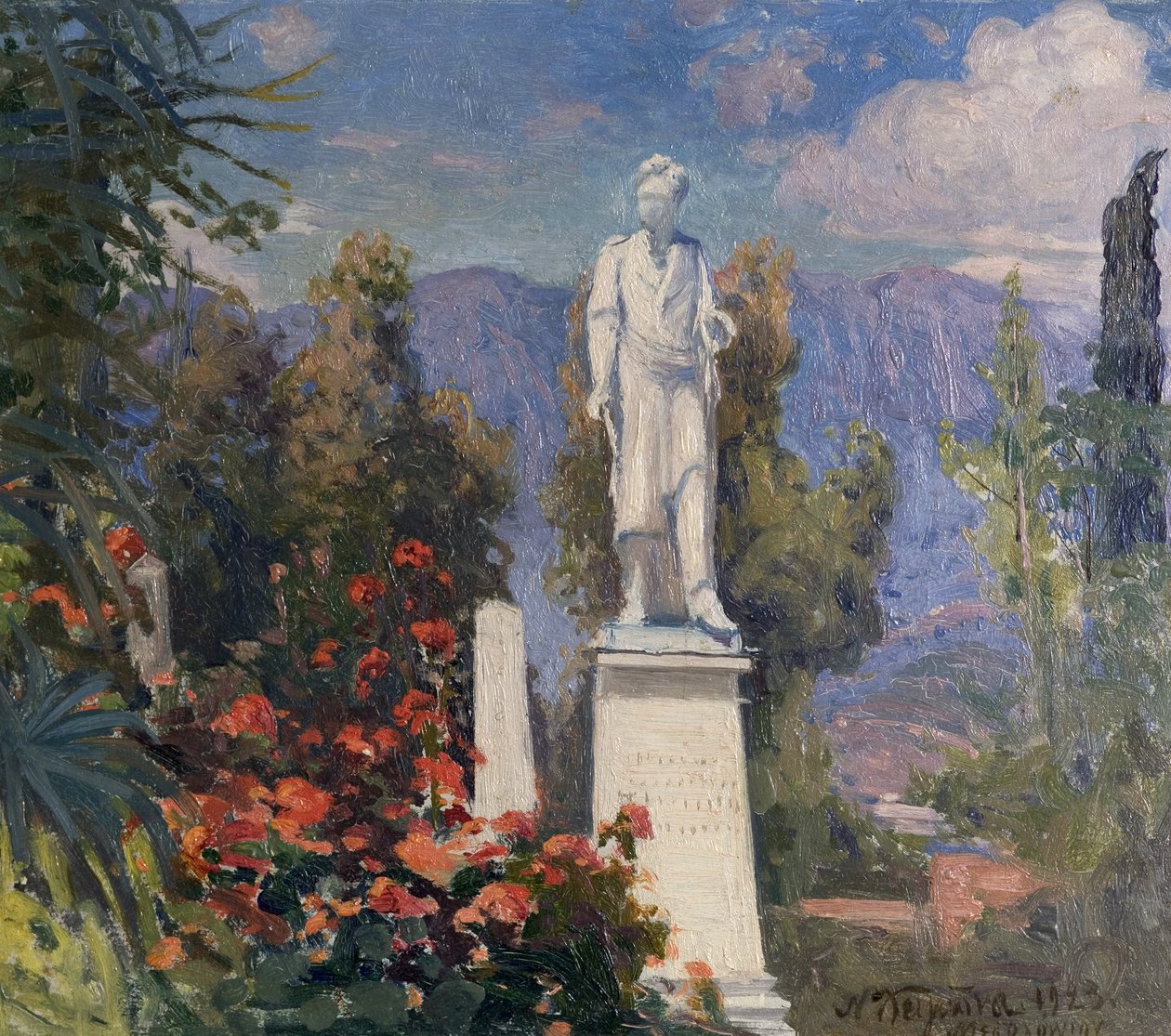

Perhaps the most dramatic expression of Byron’s historical impact lies in his involvement with the Greek War of Independence. Deeply moved by classical Greek history and contemporary Greek suffering under Ottoman rule, Byron committed not only his words but his fortune and life to the cause.

His poetry had already romanticized struggles for freedom, but his death in Greece in 1824 transformed him into a martyr for liberty. Across Europe, Byron’s sacrifice elevated the idea that poets could—and should—participate directly in historical change.

This moment resonated deeply with nationalist movements throughout the nineteenth century. Byron became a symbol of international solidarity, inspiring writers and revolutionaries who saw cultural expression as inseparable from political action.

The historical significance here is profound: Byron helped forge the modern myth of the engaged intellectual, whose moral responsibility extends beyond the page and into the world.

Moral Ambiguity and Modern Consciousness

Byron’s poetry refused easy moral resolutions. His characters are often guilty, conflicted, and self-aware; his narrators skeptical of virtue itself. In a century still deeply shaped by religious and moral absolutes, this ambiguity was unsettling—and transformative.

Historically, Byron’s refusal to moralize anticipated later developments in existential philosophy and psychological realism. His work suggests that meaning is not given but struggled for, that freedom carries consequences, and that self-knowledge is often painful.

This outlook influenced not only literature but broader cultural attitudes toward responsibility, individuality, and alienation. Byron’s poetry helped prepare readers for a world in which certainty was eroding and inner conflict was becoming central to modern identity.

Global Reach and Translation

Byron’s impact was not confined to the English-speaking world. His poetry was rapidly translated and embraced across Europe, Russia, and the Americas. In some regions, Byron was read less as a poet of personal emotion and more as a prophet of freedom and resistance.

For example, in Russia, Pushkin and Mikhail Lermontov absorbed Byron’s themes of exile and rebellion. In Italy, his work fed nationalist sentiment. Byron’s poetry resonated with independence movements in Latin America seeking cultural legitimacy alongside political autonomy.

This global circulation underscores Byron’s historical significance: he was among the first poets whose influence operated on a truly international scale, shaping literary and political consciousness across borders.

Lasting Cultural Legacy

Byron’s legacy persists not because he offered answers, but because he articulated tensions that remain unresolved: freedom versus responsibility, passion versus restraint, authenticity versus performance. His poetry gave historical form to these dilemmas at a moment when modernity itself was taking shape.

In literature, he expanded the emotional and moral range of poetic expression. His writings and personal actions shaped politics, demonstrating the power of cultural influence. Indeed, within popular culture, he helped create the enduring image of the rebellious artist. And in philosophy, he anticipated a modern sense of self defined by contradiction and struggle.

To understand Byron is to understand a turning point in cultural history—when poetry ceased to be merely ornamental or moralistic and became instead a living force within society.

Conclusion: Byron as a Historical Force

Lord Byron’s poetry mattered not only because it was beautiful or technically accomplished, but because it intervened in history. It reshaped literary form, reimagined the role of the artist, energized political movements, and articulated a new vision of the self.

Two centuries later, Byron’s voice still feels dangerously alive—restless, ironic, passionate, and unwilling to settle for easy truths. That enduring vitality is the clearest measure of his historical impact. Byron did not simply reflect his age; he helped invent the emotional and cultural language of the modern world.

When you use links on this page to make a purchase, CCM receives a modest commission. We thank you for supporting us.